What is Death? Ancient Egypt, Yama (the Osiris of Hindus), brilliant young Nachiketa, and some dead German philosophers

Death was top of mind for Ancient Egyptians. Next to the Pyramids, The Book of the Dead is what us common folk think of when we hear Ancient Egypt. In many ways, Ancient Egyptians prefigured the profound influential existential German philosopher, Martin Heidegger.

Heidegger, guide and lover to Hannah Arendt, is a world-historical name in Western thought: “His ideas have exerted a seminal influence on the development of contemporary European philosophy. They have also had an impact far beyond philosophy, for example in architectural theory literary criticism, theology, psychotherapy, and cognitive science.”

Death was a central theme of Heidegger's thought throughout his entire philosophical career. The immense popularity of Being and Time owed much to his emphasis that “preparedness for death” is a fundamental key to authentic existence – that the disclosure of authentic Being only occurs when Dasein confronts its own finitude by resolutely accepting that it is always, and inescapably, on a journey towards its own death.

The central ideas in Being and Time

Michael Watts

The Philosophy of HeideggerThe Book of the Dead has hundreds of chapters, protective magical spells, rituals and other religious liturgy appealing to the gods regarding death. The podcast History and Literature –an amazing piece of art – has an episode on it.

A famous chapter is #125: The Negative Confession. Herein, a deceased person professesess before the Egyptian god of death, Osiris, the purity of his heart:

I have not committed wrongdoing against anyone.

I have not mistreated cattle.

I have not done injustice in the place of Truth.

I do not know that which should not be be.

I have not done evil.

I have not daily made labors in excess of what should be done for me.

My name has not reached the bark of the Governor (i.e., Re).

I have not debased a god.

I have not deprived an orphan.

I have not done that which the gods abominate.

I have not slandered a servant to his superior.

I have not caused pain.

I have not caused weeping.

I have not killed.

I have not commanded to kill.

I have not made suffering for anyone.

I have not diminished the offering leaves in the temples.

I have not damaged the offering cakes to the gods.

The Literature of Ancient Egypt

Edited and introduced by William Kelly Simpson The person goes on for a while more and Osiris and the 42-member death panel end up being impressed by his case. He is spared from the wrath of death. (Note: The world-historical Pharaoh Akhenaten terminated the practice of invoking or worshipping the god of death, represented by Amun/Osiris, as part of a comprehensive religious transformation of Egyptian society toward the (monolatrous) worship of a solar-linked sole deity that was acknowledged as the transcendental/immanent sole God who provided for all nations.)

It’s not clear what Ancient Egyptians thought death meant, or why they were so obsessed with it even from a young age. In our current age, we presume death means when the body is no longer moving about and its vital signs are caput.

But the ancients did not always see things the same way. Ancient Gnostic Christians, whose hidden-away Nag Hamadi Codex was discovered in Egypt the year 1945 and who were deeply influenced by Ancient Egyptian religion similar to Judaism, believed life and death referred to the spirit (as distinct from the body and soul).

Similar to Zoroastrians, Gnostic Christians believe the material world is a struggle plane between a strong God of goodness and a malevolent lesser power and his demonic helpers who persecute humanity. Their mythology is complex, but here is their somewhat similar but somewhat sinister view of the Adam/Eve genesis story:

The archons, being the rulers of the material world, put Adam into a deep sleep, which is identified with ignorance or the lack or the lack of gnosis. They opened up his side and inserted flesh in place of the living woman that they found there, and this is probably intended as further symbolism of spirit and soul, where the woman represents the spirit that is taken away by the archons, so that Adam is once again ‘merely animate,’ possessing body and soul, but being without spirit. In The Hypostatis the female element therefore represents the spirit and is therefore higher than the male, who may stand for the soul. The archons have caused the spirit to be separated from the body of Adam, which was created by the archons, and the soul of Adam, breathed in by Ialdabaoth.

The Secret History of the Gnostics

Andrew Smith Deep sleep, death. Tomayto, tomahto?

Perhaps we will never find out what exactly the Ancient Egyptians believed about death. The mystery of death still alludes us, the year of our Lord 2025 (along with a bunch of other important things, like consciousness, the evolution of the immune system, or why quantum behavior isn’t observable in everyday life).

The closest I’ve seen to a good explanation is found in the Katha Upanishad. Upanishads are wisdom literature from Ancient India. Another famous German philosopher, the word savvy and grumpy Arthur Schopenhauer, wrote this about the Upanishads: “In the world, there is no study so beautiful and so elevating as the Upanishads. It has been the solace of my life, and will be the solace of my death.”

In this particular Upanishad, Nachiketa, a wise beyond his years young boy who was described as being “full of faith in the scriptures” is given to death by his father Vajaravasa. It’s a harsh punishment, but the Upanishad states that Vajaravasa was trying to gain religious favor by giving away his possessions. Nachiketa then asked: “What merit can one obtain by giving away cows that are too old to give milk?”

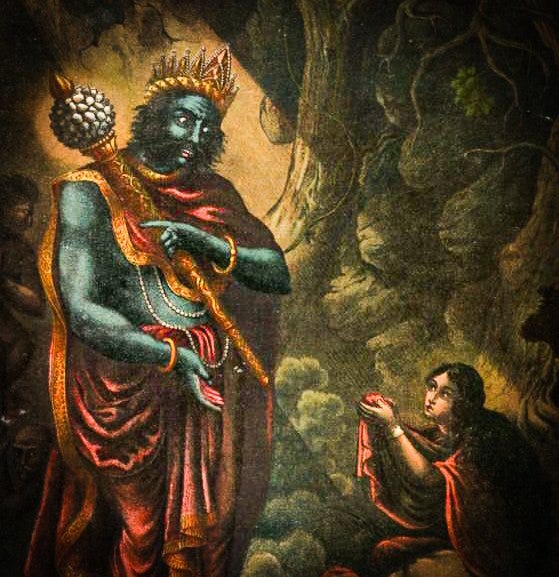

It's a long and beautiful Upanishad – you should read it – but after his father gives him up to death Nachiketa is sent to the place of Yama, the Hindu god of death (equivalent to Osiris). Yama comes late to the meeting, and as a token of apology grants Nachiketa 3 boons (favor/request).

Nachiketa is a sharp cookie and takes full advantage of the offer. Death is the topic of his third boon, where he asks:

When a person dies, there arises this doubt:

“He still exists,” say some; “He does not,” say others.

I want you to reach me the truth. This is my third boon.

Yama balks at this request:

This doubt haunted even the gods of old,

For the secret of death is hard to know.

Nachiketa, ask for some other boon.

And release me from my promise.

Nachiketa receives offers much alluring: “women of loveliness rarely seen on earth…long life…Herds of cattle…sons and grandsons who will live a hundred years…elephants and horses, gold and vast land.”

Nachiketa refuses:

Having approached an immoral like you

How can I, subject to old age and death

Ever Try to rejoice in a long life,

For the sake of senses fleeting pleasures?”

Like I said, Nachiketa is a smart cookie.

And Yama does indeed give him an answer (a very good one)

What is it?

Hmm. You’ll need to read the Upanishad yourself to find out 😊

Resources:

The Literature of Ancient Egypt edited and introduced by William Kelly Simpson

The Upanishads translated by Eknath Easwaran